For nearly four decades, wildlife biologist Al Peatt has kept a close eye on Ginty’s Pond, a wetland in the semi-arid, desert-like climate of B.C.’s Similkameen Valley. In 1990, under his leadership as one of the founding directors of the Southern Interior Land Trust (SILT), the organization acquired the property to protect its wildlife habitat and recreational values.

But in the summer of 2025, he saw the pond reach a level of depletion he had never witnessed before.

“In my 35 years of watching this wetland, I had never seen water levels this low,” Al shared. By mid-August, the inlet culvert beneath nearby VLA Road had run completely dry. This culvert normally delivers groundwater and seasonal flows into the pond throughout the year.

To Al, the shift was impossible to ignore. While small pockets of water lingered in the pond’s lower reaches, the dry culvert signaled a deeper disconnect between groundwater and surface flow. A warning of the valley’s growing hydrologic vulnerability.

A Wetland Under Pressure

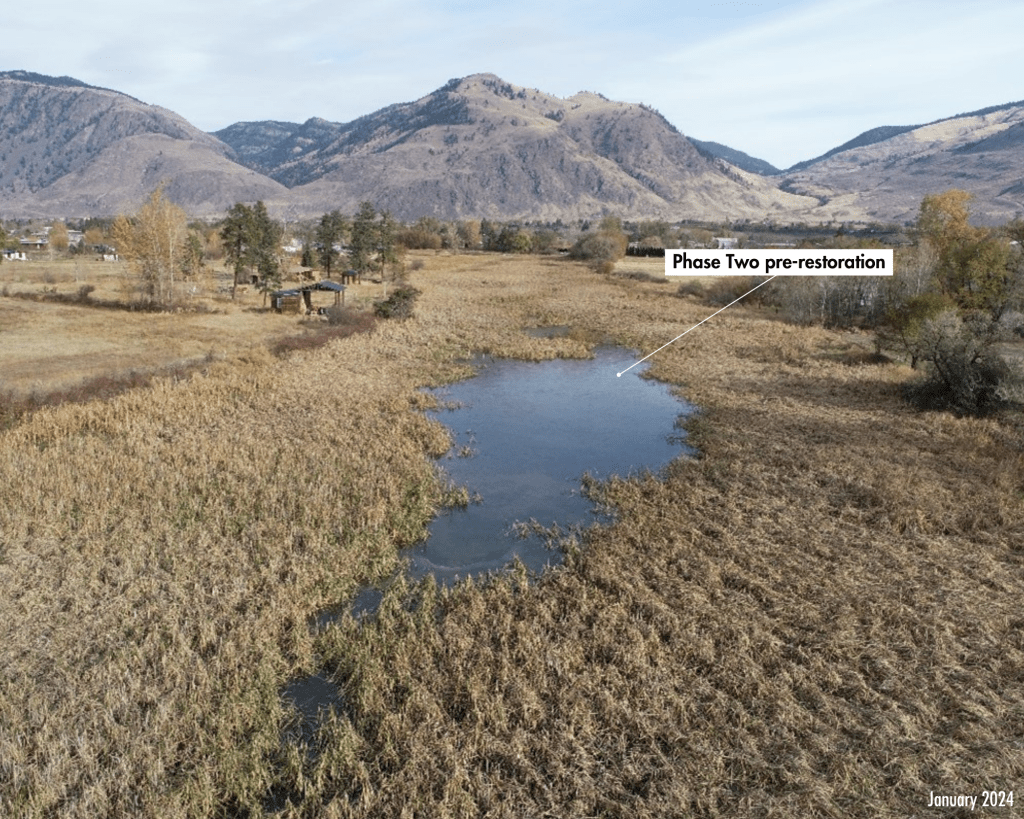

Just a few decades ago, Ginty’s Pond was almost entirely open water, alive with ducks, swans, herons, and painted turtles basking along its edges. Over time, it transformed into a dense cattail marsh, with shrinking open water and increasingly shallow pools.

Al said the reasons are complex but widely seen across the Okanagan and Similkameen. Intensive groundwater pumping for agriculture, floods that deepened the Similkameen River, spreading cattails, and long-term changes to water flow have increasingly disconnected the pond from its natural sources.

“Ginty’s is mainly fed by groundwater,” Al said. “But as the surrounding landscape and climate have changed, it’s been drying earlier and more severely every year.”

Across the region, the trend is stark. Since settlement, more than 90 percent of wetlands have been lost in the South Okanagan–Similkameen. Many of the few that remain are now limited to Indigenous reserve lands or private conservation properties. Most others have been drained, filled, or converted to agriculture.

“We’ve essentially taken away the sponges that hold and filter water in this valley,” Al said.

Restoring What Was Lost

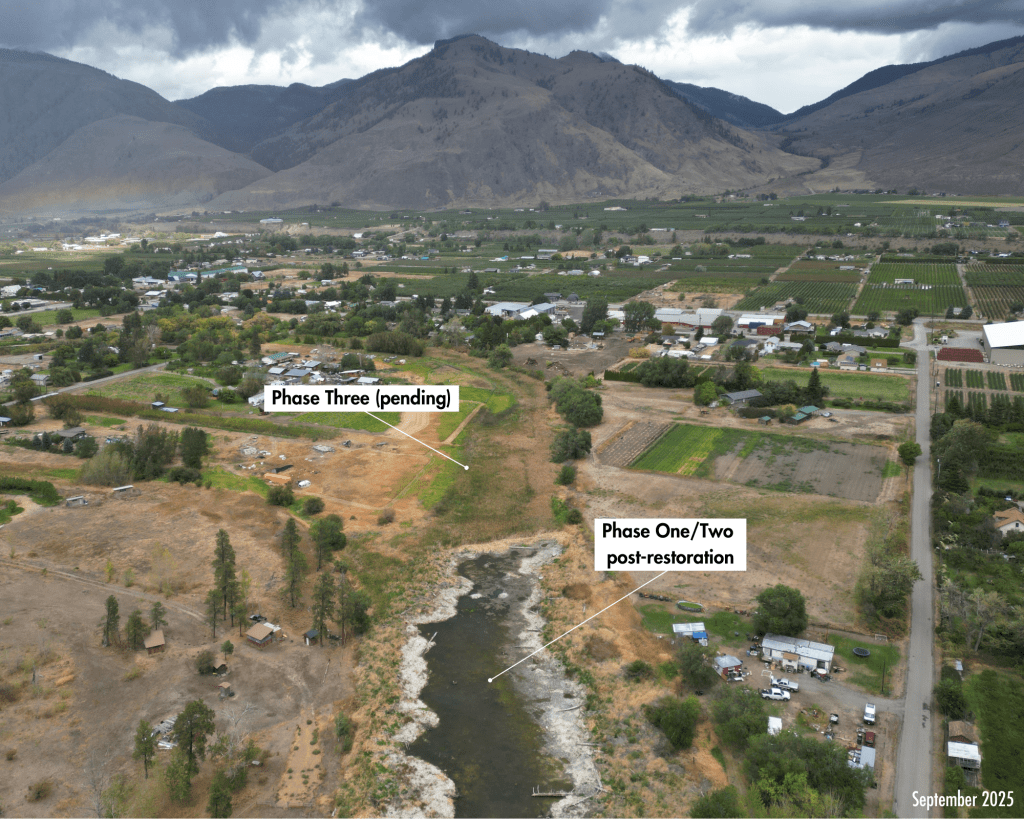

In 2022, the first Phase One of restoration at Ginty’s Pond was launched, co-led by the Southern Interior Land Trust, the Lower Similkameen Indian Band, the B.C. Wildlife Federation, and the Province of B.C.

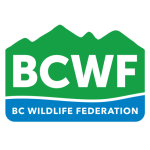

A second phase followed in 2024, focusing on deepening key sections of the wetland down to the original river bottom. By narrowing and deepening the restored channel, the project allows water to persist longer during low-flow periods like those experienced in 2025.

“We didn’t add water,” says Al. “We made the existing water more available.”

The response was immediate. Ducks returned overhead. Painted turtles reappeared. Trumpeter Swans, absent for years, were once again heard calling across the pond.

Riparian areas were replanted with native cottonwoods, snowberry, and water sedge, providing long-term shade, structure, and food.

“We’ve seen major progress in recent years as governments, nonprofits, and Indigenous communities begin to address ecosystem change and watershed resilience together,” says Al. “Everyone can relate to a watershed; it’s the lifeblood of everything.”

A Place of History and Connection

Long before the Southern Interior Land Trust acquired the property from the Cawston family, Ginty’s Pond was known as nʔaʕx̌ʷt (nah-hweet) in the syilx language. It has always been a culturally important gathering and hunting place for Indigenous peoples.

Ginty Cawston was an early pioneer in the area, and the pond was part of the family farm.

“Ginty was an avid hunter, naturalist, and outdoorsman,” Al says. “He loved the pond, and to remember him, the family wanted ‘Ginty’s’ Pond to be a place for wildlife and the community forever.”

“People used to skate on Ginty’s Pond in winter,” Al added. “It was a gathering place for everyone.”

Since restoration in 2022, the pond has held enough water during good winters to bring open water back to the site and once again offer space for the community to enjoy. When temperatures drop low enough, kids (and adults) still lace up their skates for a game of shinny on Ginty’s Pond.

Why Continued Investment Matters

Across British Columbia, wetlands like Ginty’s Pond are disappearing faster than they can be restored. Continued investment in watershed security ensures that this work does not stop when funding cycles end.

Often called the kidneys of the earth, wetlands are vital to ecosystem health. They filter pollutants, recharge groundwater, store floodwater, and help communities adapt to climate extremes by holding water longer during droughts and buffering floods when rivers rise. When restored, wetlands do more than heal landscapes. They reconnect people to nature and provide habitat for countless endangered and threatened species.

At Ginty’s Pond alone, black bear, bobcat, deer, yellow-breasted chat, western screech-owl, Lewis’s woodpecker, western painted turtle, beaver, muskrat, and numerous waterfowl all depend on the wetland. Even upland species such as spadefoot toad and tiger salamander, along with ungulates, bears, and wildcats, rely on wetlands at different stages of their lives.

“Ultimately, we need to focus on reconnecting wetland, stream, and river systems so they function as complete, resilient ecosystems,” said Al. “When that happens, it benefits everything, people, wildlife, and plants alike.”

Today, water moves quietly through the restored channel, a sign that this wetland, though stressed, is still alive. The story of Ginty’s Pond is one of renewal, but also of warning. The culvert may have run dry this year, but the work underway shows what is possible when sustained investment and strong local partnerships come together.

Thank you to our funders and project partners for making this work possible to date:

Province of British Columbia’s Watershed Security Fund, Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation, Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Nature Trust of British Columbia, the Province of British Columbia, Rewildling Water and Earth, and the Canadian Wildlife Service.

Leave a comment